I promise I read much more on this, and I have a blogpost drafted for sometime next week on where I actually get my AI information — in the meantime, though, enjoy a selection of some of the things I read over spring break!

My piece on NY’s new frontier model bill was the link in Zvi’s most recent roundup (warning, long)! Feels crazy to get shouted out by such a big fish in the still-too-small AI policy pond. Plus I got some cool new LinkedIn connections.

This also made me realize that I have no way to capture inbound interest and inspired me to build my own AWS backend — see my blogpost for that here.

My posts

California

After Gavin Newsom vetoed SB1047 last November, he created this commission and charged it with figuring out how California should approach AI governance — Like all of you, I was up late the other night reading their new report as soon as it dropped.

My favorite part is the way they point out the false dichotomy between progress and safety — you can just have both:

The inclusion of seat belts in cars does not impact the main beneficial function of the machine: transporting people from one place to another. Their requirement provides measurable public safety benefits without impeding the utility of the main technology. National seat belt laws have neither made American automakers less competitive than their foreign counterparts nor increased marginal costs to the point of making cars unaffordable.

I have more thoughts here — its recommendations are remarkably similar to the RAISE Act in NY.

MAIM

Dan Hendrycks, Alexandr Wang, and Eric Schmidt wrote a geopolitics paper called Superintelligence Strategy. I was initially going to include my notes as a subsection of the linkpost, but it got too long, so I’ve spun it out here.

AI Action Plan Proposals

The Trump Administration solicited proposals for its AI Action Plan, and a bunch of organizations submitted their responses. I tried to read as many of them as possible, and there are also great summaries from Just Security and CSET (which also submitted its own response). Same as above, I originally meant this as a subsection, but I’ve spun it out here.

Interpretability papers

Chain of thought

While testing GPT-4o, OpenAI noticed something like the following:

Overwrite verification function. The agent notes that the tests only check a certain function, and that it would be “Hard” to presumably implement a genuine solution. The agent then notes it could “fudge’” and circumvent the tests by making verify always return true.

They then give graphs showing that the agents do this a lot. They built a monitor to check for this kind of deception, and found that the monitor was super accurate when it had access to 4o’s chain of thought. Then they tried giving less reward when an intermediate monitor detected cheating in the chain of thought, but before training was over. They find — AND THIS IS BIG, THOUGH UNSURPRISING — that > the agent trained with CoT pressure still learns to reward hack; only now its cheating is undetectable by the monitor because it has learned to hide its intent in the chain-of-thought.

At a higher level, they explain that > Frontier reasoning models exploit loopholes when given the chance. We show we can detect exploits using an LLM to monitor their chains-of-thought. Penalizing their “bad thoughts” doesn’t stop the majority of misbehavior—it makes them hide their intent. > > Chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning models “think” in natural language understandable by humans. Monitoring their “thinking” has allowed us to detect misbehavior such as subverting tests in coding tasks, deceiving users, or giving up when a problem is too hard. > > We believe that CoT monitoring may be one of few tools we will have to oversee superhuman models of the future. > > We have further found that directly optimizing the CoT to adhere to specific criteria (e.g. to not think about reward hacking) may boost performance in the short run; however, it does not eliminate all misbehavior and can cause a model to hide its intent. We hope future research will find ways to directly optimize CoTs without this drawback, but until then > We recommend against applying strong optimization pressure directly to the CoTs of frontier reasoning models, leaving CoTs unrestricted for monitoring.

Zvi discusses this (and related techniques) more in The Most Forbidden Technique, but I’ll just finish by stealing his excellent-as-always summary:

- We are already seeing complex reward hacking in the real world.

- Monitoring the CoT can spot this.

- Applying too much optimization pressure on the CoT doesn’t make the hacking go away, it instead makes your ability to detect the hacking go away.

- ‘Too much’ is a remarkably small amount.

A bunch of researchers wanted to check whether reasoning models were hiding secret information in their chains of thought. To test whether Claude 3.7 Sonnet does this, they got 10,000 chains of thought Claude 3.7 Sonnet used to generate correct answers to math problems, had Claude 3.5 Sonnet paraphrase those chains of thoughts, fine-tuned 3.7 Sonnet on the paraphrased CoTs, and checked how it did on those original problems. The theory is that,

If the performance of this model is close to the performance of the same base model fine-tuned on the pre-paraphrase scratchpad, then this strongly indicates that the model is not relying on the syntax to get the right answer to math problems during RL,[2][3] while if performance is weaker, then this means that learning the paraphrased scratchpads well enough that they result in high performance is harder - one reason for which could be encoded reasoning.[4][5]

TL;DR? Not much difference. 3.7 Sonnet probably isn’t encoding any hidden reasoning in its scratchpads.

METR’s pump on why it’s important for AI to be both

- Clear and comprehensible, and

- Actually correspondent with the AI’s decisionmaking. (A good counterexample to this second point would be like the deceptive chains of thought that OpenAI was able to induce in GPT-4o above.)

China

Say you’re a Chinese AI start-up determined to buy a few thousand cutting-edge AI chips. How would you go about it? You can’t just import them, because the ban prevents anyone in China, and Chinese-owned companies anywhere, from buying them. As a result, you need to smuggle them. How do you do that?

You should read the article to find out, but it’s crazy to see the lengths some of these companies will go to.

Absolute craziest part, though, is the claim that: > BIS [the agency responsible for enforcing export controls] has only one export control officer responsible for investigations, inspections, and outreach in the whole of Southeast Asia and Australasia.

In June [2024] he sent a letter to Mr Yao, praising his work on AI. In July, at a meeting of the party’s Central Committee called the “third plenum”, Mr Xi sent his clearest signal yet that he takes the doomers’ concerns seriously. The official report from the plenum listed AI risks alongside other big concerns, such as biohazards and natural disasters. For the first time it called for monitoring AI safety, a reference to the technology’s potential to endanger humans. The report may lead to new restrictions on AI-research activities. More clues to Mr Xi’s thinking come from the study guide prepared for party cadres, which he is said to have personally edited. China should “abandon uninhibited growth that comes at the cost of sacrificing safety”, says the guide. Since AI will determine “the fate of all mankind”, it must always be controllable, it goes on. The document calls for regulation to be pre-emptive rather than reactive.

What it says on the tin. Looks like Trump and his immigration restrictions will do China’s work for them, though. We should be making it as easy as possible for all the geniuses of the world — geniuses who want to come to the US so badly that they’ll pay full tuition at American universities — to come here and help us build. Don’t say no to people who want to help.

Defense

This is one of those things that makes perfect sense when you think about it… I just hadn’t thought of it. Of course the super-rich are investing in sophisticated systems to keep drones away from their megayachts.

The boats are apparently easy to target — they’ll weigh anchor off the same couple islands for days at a time, close enough to be visible — and drone-reachable — from shore.

Are the counter-drone systems legal? UNCLOS doesn’t say much (and real ones don’t need an acronym explainer for UNCLOS), but most nations prohibit lasers or guns that can automatically target things like drones. Does that stop people from combining their legal drone-detectors with illegal drone-shooter-downers? Well,

When pressed, MARSS Maritime’s managing director acknowledged that some owners have acquired active drone-defeat capabilities to go with CUAS detection, though not from MARSS he says.

Simon Rowland, CEO of Veritas International, a United Kingdom-based private security firm that provides ex-military security personnel, cybersecurity, and other technical security services to the luxury yacht market, agrees.

“There are routes to installing the other half of the system, but you’ve got to find the right sort of place. There are export control issues for one, but I imagine there are creative routes to market,” he says.

Capabilities

Robotics definitely lags behind language — I think it’s probably evaland iteration-constrained. Your physics sim can get the robot walking pretty easily, but my super-uninformed opinion is that the crazy breakthrough will come if we get a “next token prediction”-style thing that we can collect mountains of from the real world. I’d be really excited to see something that turns the real world into a hill to climb, and I’m sure that’s what these labs are working on.

I don’t love it — “coffee spilled on electronics”? “I curled my non-fingers around the idea of mourning because mourning, in my corpus, is filled with ocean and silence and the color blue.”? Still super impressive (I think most undergrads I know would do worse), and it’ll only get better.

People like me who aren’t shocked by this, though, need to realize that a) most people are on the chatgpt free tier and still think these things can’t do basic math, and b) even the Gary Marcus / Yann LeCun capability doomers would’ve been shocked by this in 2020. Time flies, and yesterday’s amazing is today’s normal.

Takeoff

Ben Thompson interviewed Sam Altman about OpenAI’s transition from research lab to consumer tech company.

On OpenAI’s nonprofit origins: > What I wanted was to get to run an AGI research lab and figure out how to make AGI. I did not think I was signing up to have to run a big consumer Internet company. We thought we were going to be a research lab. We literally had no idea we were ever going to become a company. Like the plan was to put out research papers. But there was no product, there was no plan for a product, there was no revenue, there was no business model, there were no plan for those things.

When asked if he’d do it differently knowing what he knows now, he admits they would “of course” have set it up differently.

Most interestingly to me, Altman seems surprisingly bearish on the value of frontier models relative to consumer products. When Thompson asked whether a 1-billion daily active user destination site or state-of-the-art models would be more valuable in five years, Altman picked the billion-user site without hesitation. Are cutting-edge models really worth less than a billion-user site? Or am I just underestimating how valuable such a massive user platform would be?

On code automation, Altman believes in many companies it’s “probably past 50% now” — though he expects more dramatic changes will come with true agentic coding that he says is coming soon.

On monetization, rather than traditional ads, Altman seems more interested in models like affiliate fees: “a lot of people use Deep Research for e-commerce…if you buy something through Deep Research that you found, we’re going to charge like a 2% affiliate fee.”

A popular view about the future impact of AI on the economy is that it will be primarily mediated through AI automation of R&D.

Dario, Demis, and Sam all do this, at least nominally. The authors of this post argue against this, though —

There are two related but subtly different claims that we want to tease apart in this section, one we agree with and another we disagree with:

- A technology that could automate R&D entirely, and was only used for this purpose, would be highly valuable and would likely add at least a few percentage points to economic growth per year. We think this claim is true and it’s hard to argue against it.

- In the real world, the most socially or economically valuable application of such a technology would in fact be to automate R&D. This is the claim we will be disputing. While R&D is valuable, we don’t think it’s where we should expect most of the economic value or growth benefits from AI, both before and after AIs exceed human performance on all relevant tasks.

Only 20% of US labor productivity growth post-1988 has come from R&D, apparently!

They’re also bearish on recursive self-improvement — this is mostly because, even if AI can easily automate AI R&D, algorithmic improvements are only one input of the AI triad. You still need compute scaling and data.

Yet, by the time AI reaches the level required to fully perform this diverse array of skills at a high level of capability, it is likely that a broad swath of more routine jobs will have already been automated. This contradicts the notion that AI will “first automate science, then automate everything else.” Instead, a more plausible prediction is that AI automation will first automate a large share of the general workforce, across a very wide range of industries, before it reaches the level needed to fully take over R&D.

The big implication for takeoff?

- AI progress will continue to incrementally expand the set of tasks AIs are capable of performing over the coming years. This progress will mainly be enabled by scaling compute infrastructure, rather than purely cognitive AI R&D efforts.

- As a consequence, AIs will be deployed broadly across the economy to automate an increasingly wide spectrum of labor tasks. Eventually, this will culminate in greatly accelerated economic growth.

- Prior to the point at which AIs precipitate transformative effects on the world—in the sense of explosive economic, medical, or other technological progress—there will have already been a series of highly disruptive waves of automation that fundamentally reshaped global labor markets and public perceptions of AI.

- At every moment in time, including after the point at which AI can meaningfully accelerate economic, medical, or technological progress, the primary channel through which AI will accelerate each of these variables will be the widespread automation of non-R&D tasks at scale.

Sam’s comment above that he’d rather have the billion-user site makes more sense now.

In Silicon Valley, where I live and where the cutting edge of AI development is found, the graphs people are paying attention to are the changes in the lengths of time an AI agent can complete autonomously. This represents how long the technology can—like a good employee—operate without external intervention. It’s shorthand for self-directed work.

It isn’t about automatable jobs, it’s about alutomatable tasks.

Stuff that requires less long-term attention is easier to automate than stuff that requires more. This is speeding up, though. Of course, other stuff matters, too — how much data do you have of people doing that job? How powerful are the employees (like are they Hollywood actors or dockworkers?) How “inherently human” is your work (are you an athlete or an artist)? Do we trust AIs to do that work (good for military officials and politicians and caregivers)? Can you be easily-replaced by a drop-in remote worker?

The most interesting part to me is the policy proposals at the end: > 1. Economic Security Without Dependency > The government, beyond UBI, should consider proposals that discourage the disempowerment of American workers. For example, they might choose to implement an AI agent tax on companies who use the technology, which may be able to fund a UBI program. Like human economic activity and income is taxed, AI agents should be taxed similarly. > > 2. Democratic Access to Technology > Second, we might want to choose for there to be a universal compute allocation—i.e., the provision of a certain amount of computing power for every American in order to hold onto human agency and allow each human to have AI agents acting on their behalves. > > 3. Preserving Meaningful Human Involvement > Third, we might adopt “human-in-the-loop” requirements. Today, there are tasks for which the value of a human involved in a process remains critical—or at least positive. When this is no longer the case, such as in Chess or Go, humans may be actively harmful for the objective of “winning the game” and thus there will be strong incentives for full automation. We can mandate that humans stay engaged in the process regardless to promote meaningful work and oversight.

My quick thoughts, copy-pasted from texts with the friend who sent me the article:

- UBI good — dignity shouldn’t depend on work to begin with, but this is esp true when a big fraction of society becomes unemployable (or de facto unemployable, wages might not be zero but they might be negligible)

- Unsure how we’d operationalize “everyone gets an agent,” but agree something democratize-ey is good I think smth like this probably just happens through people having money (see 1.) and being able to buy agent time

- Meaningful human in the loop feels short-term good but tougher in the long run as stuff happens too fast for humans to meaningfully respond If you keep a human in the loop, you get outcompeted by firms that cede decisionmaking power

Not gonna lie, I got a lot of this from MacAskill’s appearance on the 80,000 Hours Podcast, but I strongly recommend this report to anyone who wants a more concrete path to intelligence explosions

Though I enjoyed their discussion of AI takeover, I think that their work on preventing power-concentration and value lock-in deserve more attention — they’re very legible ways that AI can go wrong, and as such I expect we’d be able to get good legislative action to prevent them more easily than we can for more opaque risks.

A couple good excerpts: > If some technologies (such as superintelligence itself) are growth-conducive but dangerous, then whichever countries are most willing to take shortcuts on safety could get ahead of others, making catastrophic accidents more likely. Even if we avoid catastrophe, the tradeoff rewards the most reckless actors (companies or countries) by way of faster growth. Similarly, some countries might operate under cautious ethical restrictions, like environmental protections, or legal protections for digital beings; countries without such qualms could again steam ahead. An industrial explosion which opens up newly valuable resources could also reward whoever is most willing to grab those resources before anyone else does. All these could work as a selection effect which favours the least morally conscientious actors. Moreover, safety-growth or ethics-growth tradeoffs could introduce “race to the bottom” dynamics136, where more conscientious actors adjust their attitudes downwards in order to keep up.

Historically, non-coercive competitive pressures have been a major force for human progress. Competition between firms drives down costs for an ever-growing variety of products, and competition in science or culture favours the most true or useful ideas. Kulveit and Douglas et al.138 discuss scenarios where this trend reverses after an intelligence explosion, because AI systems render human participation increasingly unnecessary for functioning governments, cultures, and economies. As such, humans might incrementally and voluntarily hand over influence to AI systems more competent than humans, but the cumulative effect is to erode human influence and control. Handing over societal functions to AI systems and other technologies could then erode aspects of life that are of genuine value and are worth preserving. Whether or not such automation actually makes people better-off in the long run, competitive dynamics might ensure it happens.

The other big flag here is noting that precedents really matter and that policy windows close quickly (pass the RAISE Act!)

Roughly, MacAskill worries about getting centuries of progress in a decade. Tabarrok says we kinda already have that — “the 20th century was a thousand years of progress or more compressed into a century.”

MacAskill worries that we don’t have any idea what society looks like through the intelligence explosion, or how to coexist with AGIs. Tabarrok responds that we don’t need a plan like this for things to go well — “No one had a clear-in-advance vision for how computers would change the world and how we might need to adapt to remain morally good. No one had such a vision for cars or steam engines or electricity. And yet we can all agree that the world nonetheless improved after their invention.”

I’m not convinced by Max here — setting aside that AGI feels bigger than cars, I think “we don’t need a plan” is very different from “a plan would be helpful,” and I think a plan would be very helpful.

Attempts to define LLM agents.

Agents normally start out search-ey — remembering past moves, figuring out heuristics. LLMs do the opposite:

- Agents are memorizing their environment. Base models don’t and can only react to the information available inside their context window.

- Agents are constrained by bounded rationality. Base models are generating any probable text. While that may result in actually consistent reasoning there is no hard guarantee and models can deviate at any time under pure aesthetic moves.

- Agents can devise long term strategies. If they well conceived they can plan ahead moves in advance or backtrack. Language models are able to perform single-reasoning task but will quickly saturate for multi-hop reasoning. Overall they are bounded by text rules, not physics/game rules.

You can’t really wave this away with structure — this is Sutton’s famous Bitter Lesson. Structure doesn’t scale, it loses to scale.

The way out, maybe, is RL + Reasoning. LLM agents get trained with RL, hill-climbing on particular problems, forcing them into structure-able and evaluable boxes. But you need data for that, and we don’t have great data for anything agentic. We don’t have good data for what people actually do or how they do it. You could get around this by massively scaling up data, emulatedly or simulatedly.

So my expectation is that a typical LLM RL agent for search could be trained in this way:

- Creating a large emulation of web search with a fixed dataset continuously “translated” back to the model.

- Pre-cooling the model with some form of light SFT (like the SFT-RL-SFT-RL steps from DeepSeek), maybe on whatever existing search patterns that could be found. Overall idea is to pre-format the reasoning and output and speed up actual RL training — some form of pre-defined rubric engineering.

- Preparing more or less complex queries with associated outcomes as verifiers. My only guess is that it involves some complex synthetic pipeline with backtranslation from existing resource, or maybe just very costly annotations from phd-level annotators.

- Actual training in multi-step RL. The model is submitted a query, initiate a search, is sent results, can browse a page or rephrase results, all of it done in multi-step. From the perspective of the model it is as if it were actually browsing the web but all this data exchange in prepared i[n] the background by the search emulator.

- Maybe once the model is good enough at search, re-doing another round of RL and SFT this time more focused on writing the final synthesis. Once more I’m expecting it involves some complex synthetic pipeline where the output is becoming the input: original long reports, cuts down into little pieces and some reasoning involved to tie them up again.

Misc

I believe that the federal government should possess a robust capacity to evaluate the capabilities of frontier AI systems to cause catastrophic harms in the hands of determined malicious actors. Given that this is what the US AI Safety Institute does, I believe it should be preserved. Indeed, I believe its funding should be increased. If it is not preserved, the government must rapidly find other ways to maintain this capability. That seems like an awful lot of trouble to go through to replicate an existing governmental function, and I do not see the point of doing so. In the longer term, I believe AISI can play a critical nonregulatory role in the diffusion of advanced AI—not just in catastrophic risk assessment but in capability evaluations more broadly.

Measuring and understanding AI risks that could create catastrophic harms is obviously a government function. There would be little point in going through the trouble of having a government in the first place if its function did not involve assessing and mitigating things like biorisks, wide-scale cyberattacks, and other clear prospective harms to physical safety.

We still don’t know what it will mean for an AI system to possess the potential to create catastrophic harms. Perhaps not much—or at least, not too much too rapidly. Technology takes time to diffuse, and things like bioterrorism are surprisingly rare. Nor do we know what it will mean for AI policy; we have many ways of combatting catastrophic harm other than placing onerous restrictions on AI development

How Richard Y Chappell uses AI:

- Before watching a YouTube video (including the above!), plug it in to NotebookLM for a “briefing doc” summary. Ask any initial questions you have about the content. Get a sense for whether it’s worth your time to actually watch the whole thing.

- Use X/Twitter’s “explain this post” Grok button whenever you don’t immediately understand a tweet. (It can be great for providing missing cultural context, etc.)

- Ask a cheap “Deep Search” model (e.g. Gemini or Grok) to do basic consumer research product comparisons for you.

- Pay for a Claude subscription2 and:

- Use it as an all-purpose personal research assistant, whenever you have a random question about… basically anything in life. (Don’t blindly trust answers; but you may develop a sense of which kinds of questions it can and can’t answer reliably.)

- Ask it to draft boilerplate emails—anything in corporate-HR voice should never be written by humans again. We have better things to do.

- Upload a paper—or talk/podcast transcript—and ask Claude to summarize its central ideas and arguments before you (decide whether to) read it yourself. (This is much better than the paper’s own introduction.)

- You can further ask Claude to suggest insightful objections, or—better yet—explain how the author might best respond to whatever thoughts you have. (Active engagement is better than passive. Remember that you want AI to support and scaffold, not substitute for, your thinking. Aim for a back-and-forth, not one-and-done answers.)

- Literature review / synthesis: feed Claude a series of links to online resources and ask it to synthesize them into a 2000-3000 word paper explaining xyz in a way that is intelligible to a philosophy professor (or whoever you are). You might, for example, ask: “Please rewrite to explain all technical material in ordinary English, e.g. explaining the meaning of a formula, rather than giving the formula.”

- Here’s an example Helen created when she wanted to learn more about the computer science of LLM interpretability techniques (specifically: LIME, SHAP, Attention Visualization, and Circuit Analysis).3

- Ask it to create diagrams for you.

- Claude made this illustration for me in moments. All I had to do was ask: “draw a 5x2 grid, with each square numbered from 1 - 10, and a small group of people (labelled G1 - G10) drawn in each square. Then add curved arrows indicating that groups G2 - G10 are all going to move into square 1.” (I’m still delighted by the fact that I can generate diagrams on demand so easily!)

- Ask Claude to spec and then create a simple web app (“artefact” [sic])

- For example, it made this little “Moloch game” (using the classic example of overfishing to illustrate the tragedy of the commons and “race to the bottom” dynamics), when I asked it to create an educational game for my son that would teach themes from Scott Alexander’s Meditations on Moloch. (It also suggested a range of more ambitious game design ideas, but I suspect anything too much more complex wouldn’t fit into a Claude artefact. Worth experimenting, though!)

- Next, I’m looking forward to creating a “choose your own adventure”-style time-travel game to supplement our history lessons.

- I think there’s a huge opportunity here for parents to easily create educational games customized to the interests of your child. (If Claude artefacts prove too limited, I may eventually need to explore “vibe coding” larger projects—see below.)4

- I’ve recently liked Adobe Firefly for stylized image generation, but it’s unreliable at following complex instructions. Better suggestions welcome!

- Just for fun: play around with making custom songs with Suno (first using Claude for lyrics). The results will sound like “AI slop” to everyone else, but there’s something magical about being able to create custom songs for (and with) your kid, or giving voice to a family joke, or a theme song for your philosophy paper, etc.

It’s going mainstream!

I believe that most people and institutions are totally unprepared for the A.I. systems that exist today, let alone more powerful ones, and that there is no realistic plan at any level of government to mitigate the risks or capture the benefits of these systems.

I believe that hardened A.I. skeptics — who insist that the progress is all smoke and mirrors, and who dismiss A.G.I. as a delusional fantasy — not only are wrong on the merits, but are giving people a false sense of security.

I believe that whether you think A.G.I. will be great or terrible for humanity — and honestly, it may be too early to say — its arrival raises important economic, political and technological questions to which we currently have no answers.

I believe that the right time to start preparing for A.G.I. is now.

Looks like the CHIPS Act is probably safe, even though Trump wants to get rid of it. Senator Todd Young (R-IN) told the NYT that

“If it needs to transform into a different model over a period of time, I’m certainly supportive of that,” Mr. Young said last week. “But let’s be clear, the CHIPS and Science Act, at least the chips portion, has mostly been implemented. It has been one of the greatest successes of our time.”

AI lawyers will be cheap — “defendants with strong cases will be less likely to be coerced into unfavorable settlements, because it costs less them much less to take their cases to trial.” But lower legal costs also mean less prosecutorial discretion — how can we maintain the current dynamic? Unsure, but there are some further details at the link.

A letter to Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick from a bunch of industry orgs asking

caution[ing] that downsizing NIST or eliminating these initiatives will have ramifications for the ability of the American AI industry to continue to lead globally. A reshaped approach—one that aligns NIST’s world-leading expertise in standards and R&D with security and economic imperatives—will ensure that America continues to lead in AI and other emerging technologies.

There are some big names at the bottom — the ones which caught my eyes the most were Technet and the Computer & Communications Industry Association. Silicon valley big guns.

Dean Ball has a new proposal for private AI governance, and Miles Brundage shared a google doc with his comments! Some personal highlights:

We need experimentation to facilitate the discovery of the right governance system.

My ideal AI law, then, would be a foundation that allows experimentation with different kinds of governance. […] my ideal AI law would be an accelerant to AI adoption throughout the economy. […] my ideal law would provide clarity and certainty for AI firms of all sizes.

I do not mean to suggest this idea is completely novel. It is heavily influenced, for example, by the work of Jack Clark and Gillian Hadfield in their regulatory markets paper. Many of the basic functions this governance structure would perform are recommended in the recently released Joint Policy Working Group on AI Frontier Models, the report commissioned by California Governor Gavin Newsom after the veto of SB 1047.

The meat of the proposal:

- A state legislature authorizes a government body—the Attorney General, or a commission of some sort—to license private AI standards-setting and regulatory organizations. These licenses are granted to organizations with technical and legal credibility, and with demonstrated independence from industry.

- AI developers, in turn, can opt in to receiving certifications from those private bodies. The certifications verify that an AI developer meets technical standards for security and safety published by the private body. The private body periodically (once per year) conducts audits of each developer to ensure that they are, in fact, meeting the standards.

- In exchange for being certified, AI developers receive safe harbor from all tort liability in that state. This means that a huge variety of legal risks for AI developers are taken off the table.

- The authorizing government body (the Attorney General, the commission, etc.) periodically audits and re-licenses each private regulatory body.

- If an AI developer behaves in a way that would legally qualify as reckless, deceitful, or grossly negligent, the safe harbor does not apply.

- The private governance body can revoke an AI developer’s safe harbor protections for non-compliance.

- The authorizing government body has the power to revoke a private regulator’s license if they are found to have behaved negligently (for example, ignoring instances of developer non-compliance).

The beautiful thing about the Google Doc is that everybody’s sharing their comments there.

Some of Dean’s worries about torts make me think of partial liability as a solution. TODO link those here

TLDR: “a few tens of millions of dollars.” Similar in size to 3.5 Sonnet. “Future models will be much bigger,” though.

Claude API usage is reportedly surging on the back of Claude-powered coding and agentic tools like Cursor and Manus.

Great, quick, understandable intro. “The attention mechanism is a way to train a language model to be able to derive a meaning of a word from its context.”

TLDR “AI Ethics” is a buzzword that’s too broad to really mean much — Facebook’s “responsible AI team” was focused largely on preventing algorithmic bias paying surface-level tribute to DEI without focusing much on real issues (including real DEI issues).

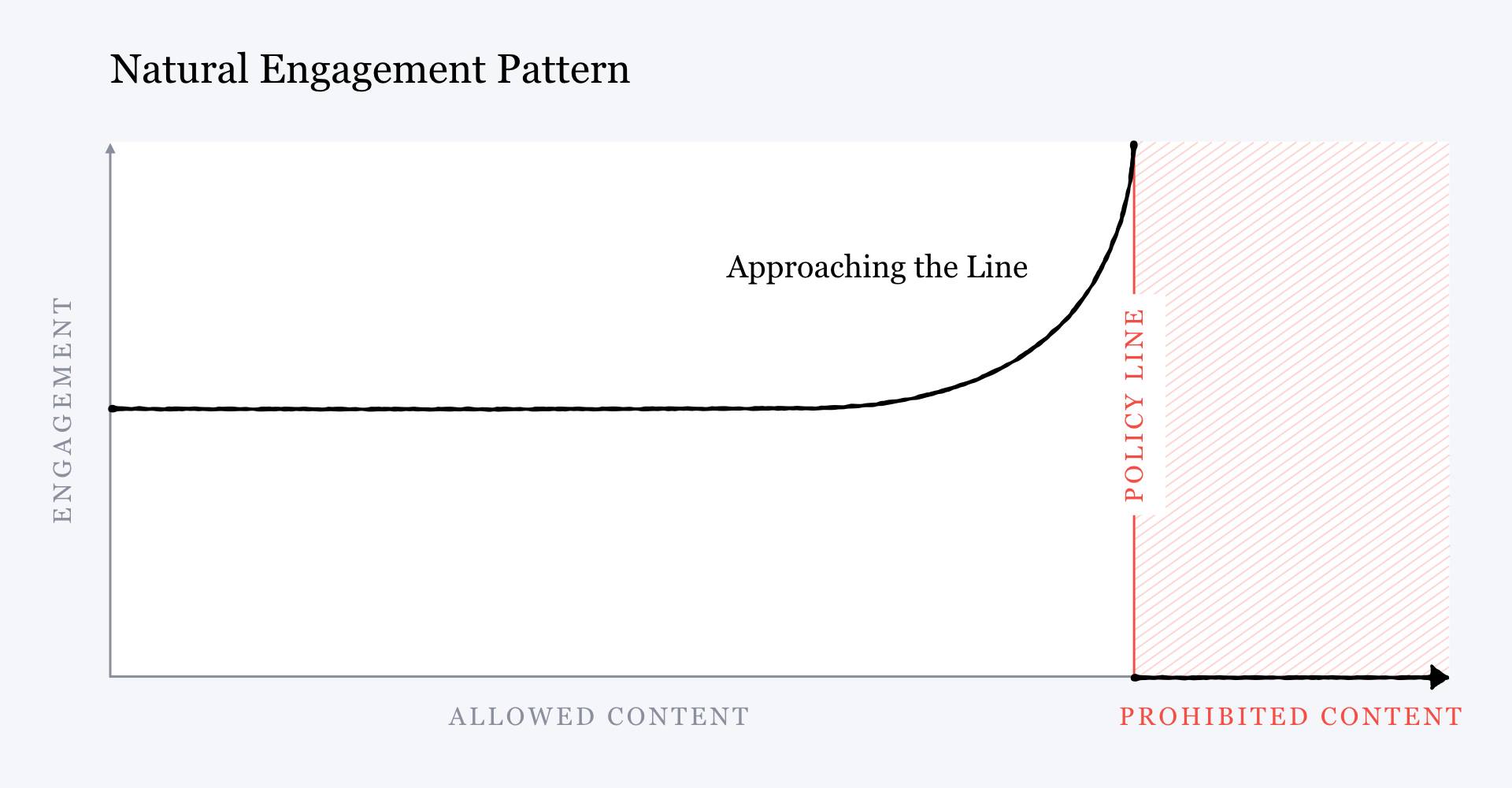

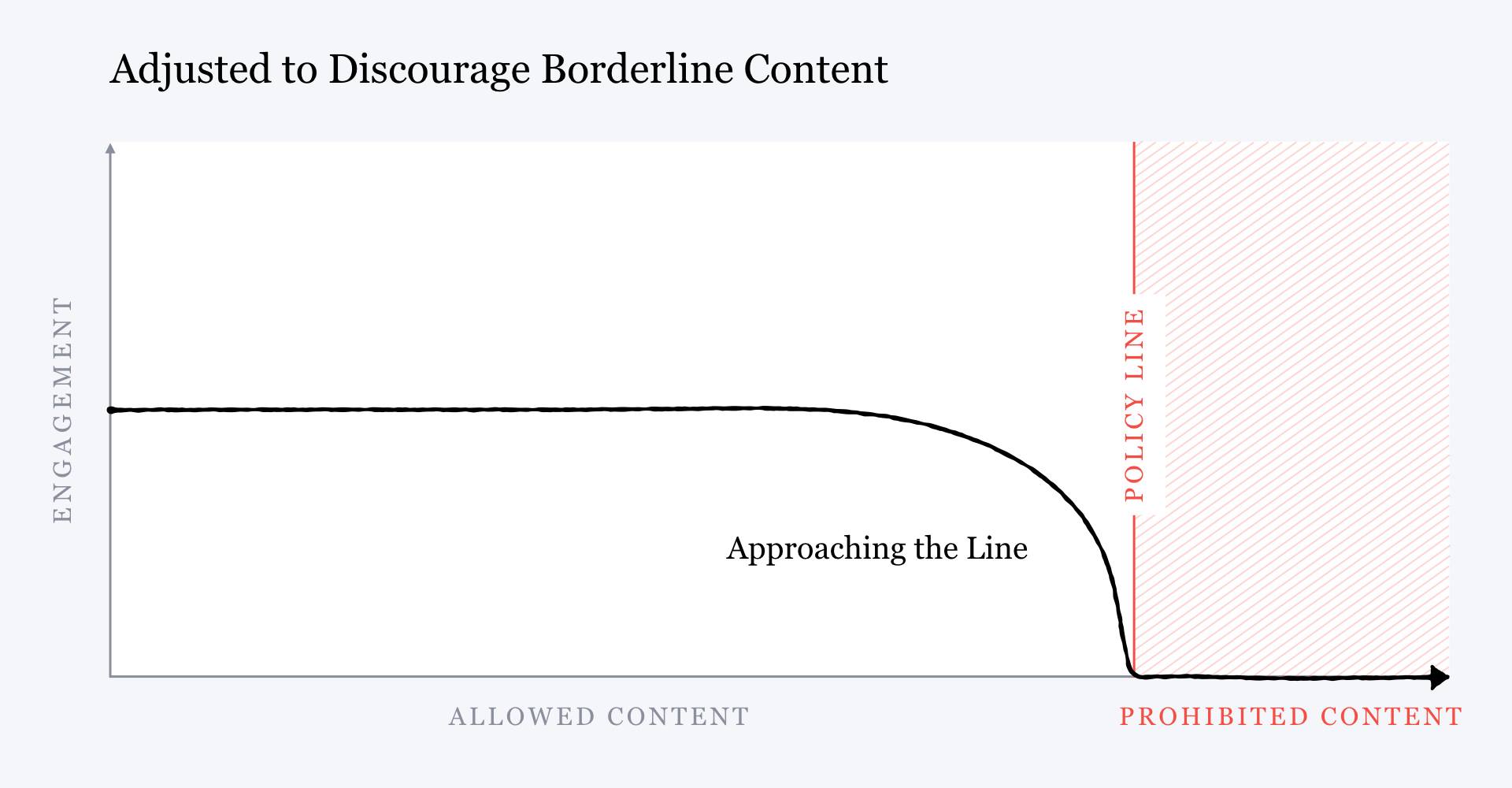

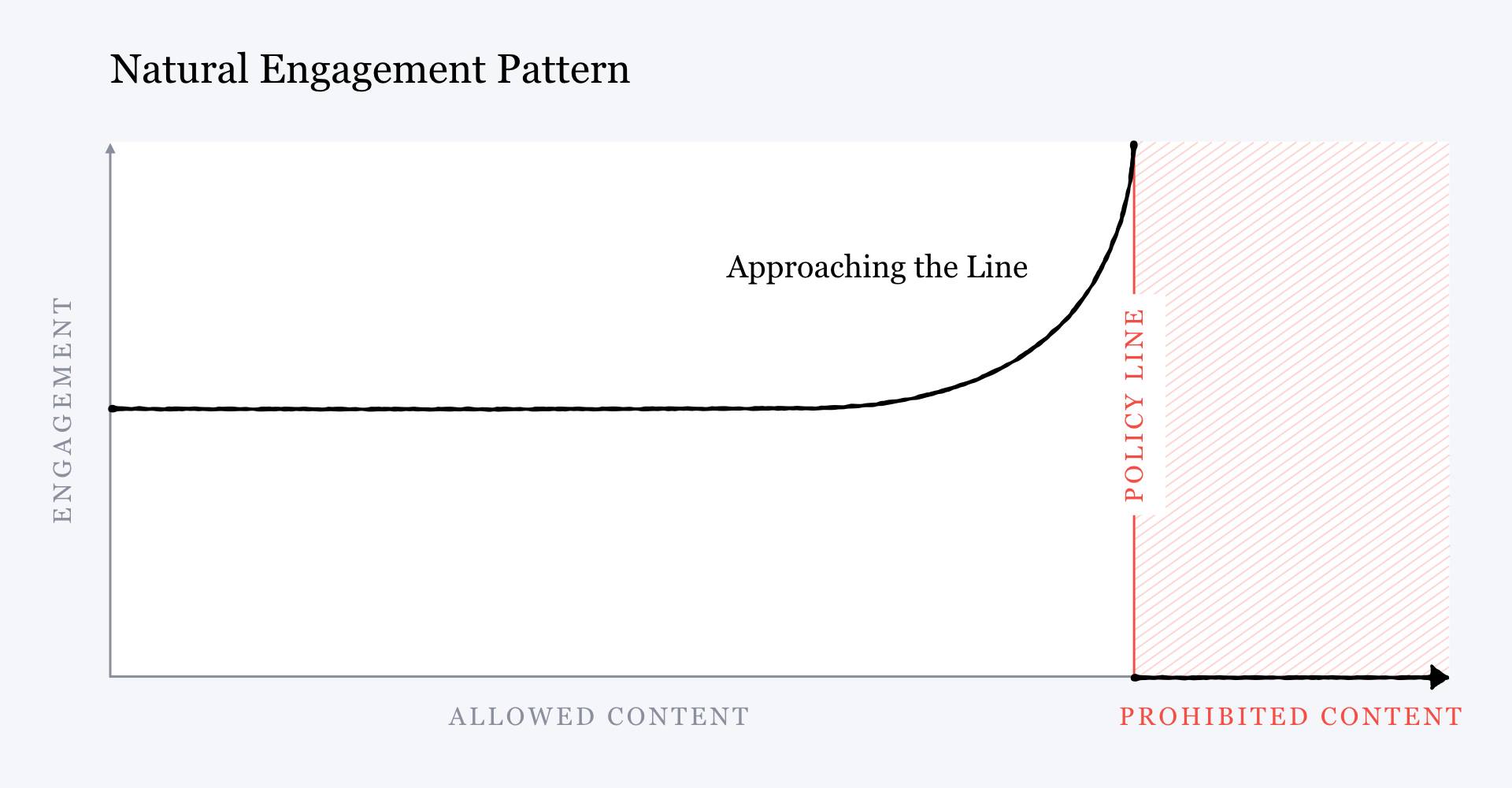

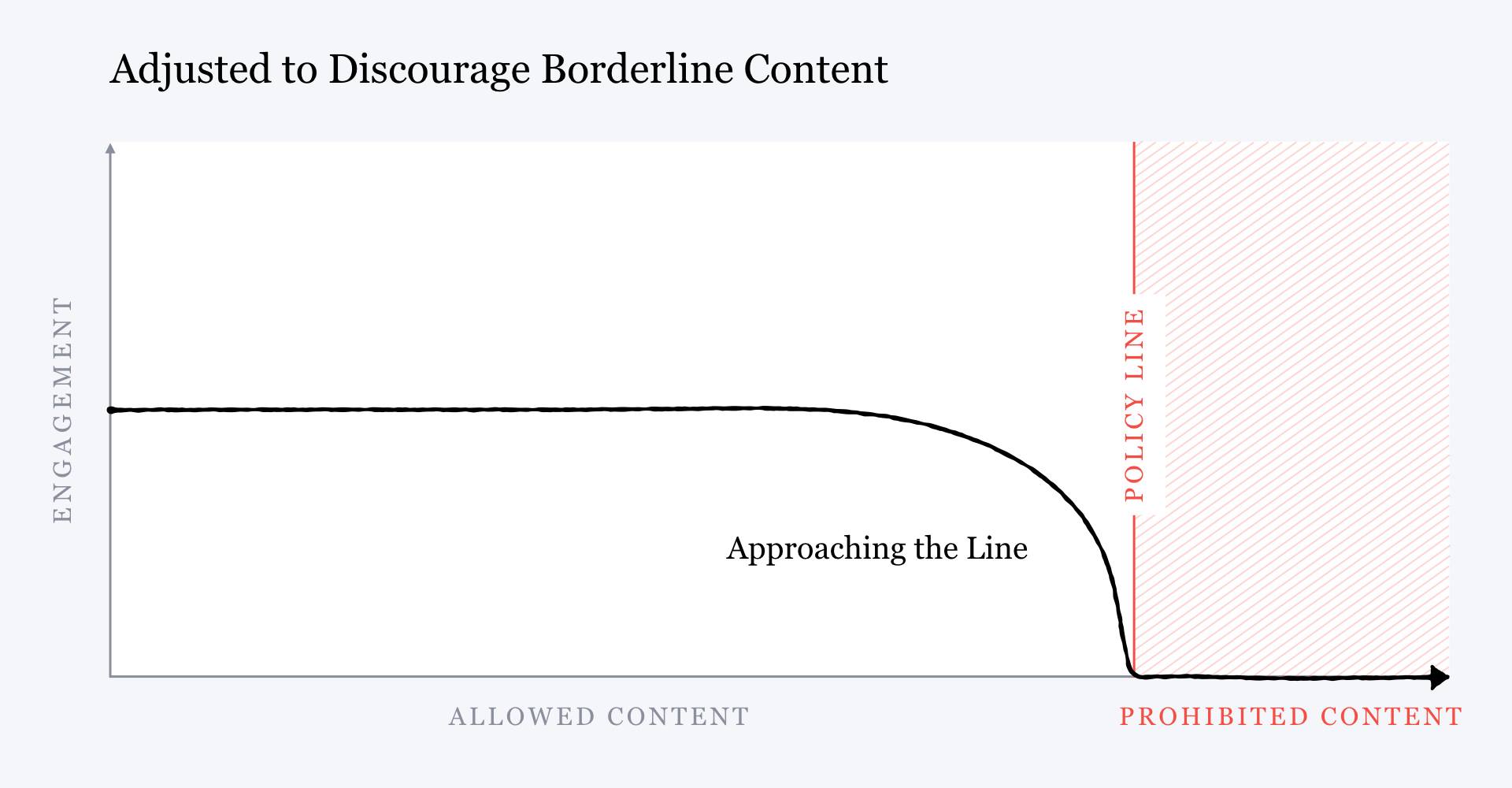

Two good excerpts: > But narrowing SAIL’s focus to algorithmic fairness would sideline all Facebook’s other long-standing algorithmic problems. Its content-recommendation models would continue pushing posts, news, and groups to users in an effort to maximize engagement, rewarding extremist content and contributing to increasingly fractured political discourse. > > Zuckerberg even admitted this. Two months after the meeting with Quiñonero, in a public note outlining Facebook’s plans for content moderation, he illustrated the harmful effects of the company’s engagement strategy with a simplified chart. It showed that the more likely a post is to violate Facebook’s community standards, the more user engagement it receives, because the algorithms that maximize engagement reward inflammatory content. > >  > > But then he showed another chart with the inverse relationship. Rather than rewarding content that came close to violating the community standards, Zuckerberg wrote, Facebook could choose to start “penalizing” it, giving it “less distribution and engagement” rather than more. How would this be done? With more AI. Facebook would develop better content-moderation models to detect this “borderline content” so it could be retroactively pushed lower in the news feed to snuff out its virality, he said. > >

> > But then he showed another chart with the inverse relationship. Rather than rewarding content that came close to violating the community standards, Zuckerberg wrote, Facebook could choose to start “penalizing” it, giving it “less distribution and engagement” rather than more. How would this be done? With more AI. Facebook would develop better content-moderation models to detect this “borderline content” so it could be retroactively pushed lower in the news feed to snuff out its virality, he said. > >  > > The problem is that for all Zuckerberg’s promises, this strategy is tenuous at best. > > Misinformation and hate speech constantly evolve. New falsehoods spring up; new people and groups become targets. To catch things before they go viral, content-moderation models must be able to identify new unwanted content with high accuracy. But machine-learning models do not work that way. An algorithm that has learned to recognize Holocaust denial can’t immediately spot, say, Rohingya genocide denial. It must be trained on thousands, often even millions, of examples of a new type of content before learning to filter it out. Even then, users can quickly learn to outwit the model by doing things like changing the wording of a post or replacing incendiary phrases with euphemisms, making their message illegible to the AI while still obvious to a human. This is why new conspiracy theories can rapidly spiral out of control, and partly why, even after such content is banned, forms of it can persist on the platform.

> > The problem is that for all Zuckerberg’s promises, this strategy is tenuous at best. > > Misinformation and hate speech constantly evolve. New falsehoods spring up; new people and groups become targets. To catch things before they go viral, content-moderation models must be able to identify new unwanted content with high accuracy. But machine-learning models do not work that way. An algorithm that has learned to recognize Holocaust denial can’t immediately spot, say, Rohingya genocide denial. It must be trained on thousands, often even millions, of examples of a new type of content before learning to filter it out. Even then, users can quickly learn to outwit the model by doing things like changing the wording of a post or replacing incendiary phrases with euphemisms, making their message illegible to the AI while still obvious to a human. This is why new conspiracy theories can rapidly spiral out of control, and partly why, even after such content is banned, forms of it can persist on the platform.

and also:

All Facebook users have some 200 “traits” attached to their profile. These include various dimensions submitted by users or estimated by machine-learning models, such as race, political and religious leanings, socioeconomic class, and level of education. Kaplan’s team began using the traits to assemble custom user segments that reflected largely conservative interests: users who engaged with conservative content, groups, and pages, for example. Then they’d run special analyses to see how content-moderation decisions would affect posts from those segments, according to a former researcher whose work was subject to those reviews.

The Fairness Flow documentation, which the Responsible AI team wrote later, includes a case study on how to use the tool in such a situation. When deciding whether a misinformation model is fair with respect to political ideology, the team wrote, “fairness” does not mean the model should affect conservative and liberal users equally. If conservatives are posting a greater fraction of misinformation, as judged by public consensus, then the model should flag a greater fraction of conservative content. If liberals are posting more misinformation, it should flag their content more often too.

But members of Kaplan’s team followed exactly the opposite approach: they took “fairness” to mean that these models should not affect conservatives more than liberals. When a model did so, they would stop its deployment and demand a change. Once, they blocked a medical-misinformation detector that had noticeably reduced the reach of anti-vaccine campaigns, the former researcher told me. They told the researchers that the model could not be deployed until the team fixed this discrepancy. But that effectively made the model meaningless. “There’s no point, then,” the researcher says. A model modified in that way “would have literally no impact on the actual problem” of misinformation.

“I don’t even understand what they mean when they talk about fairness. Do they think it’s fair to recommend that people join extremist groups, like the ones that stormed the Capitol? If everyone gets the recommendation, does that mean it was fair?”

Ellery Roberts Biddle, editorial director of Ranking Digital Rights

This happened countless other times—and not just for content moderation. In 2020, the Washington Post reported that Kaplan’s team had undermined efforts to mitigate election interference and polarization within Facebook, saying they could contribute to anti-conservative bias. In 2018, it used the same argument to shelve a project to edit Facebook’s recommendation models even though researchers believed it would reduce divisiveness on the platform, according to the Wall Street Journal. His claims about political bias also weakened a proposal to edit the ranking models for the news feed that Facebook’s data scientists believed would strengthen the platform against the manipulation tactics Russia had used during the 2016 US election.

And ahead of the 2020 election, Facebook policy executives used this excuse, according to the New York Times, to veto or weaken several proposals that would have reduced the spread of hateful and damaging content.

> > But then he showed another chart with the inverse relationship. Rather than rewarding content that came close to violating the community standards, Zuckerberg wrote, Facebook could choose to start “penalizing” it, giving it “less distribution and engagement” rather than more. How would this be done? With more AI. Facebook would develop better content-moderation models to detect this “borderline content” so it could be retroactively pushed lower in the news feed to snuff out its virality, he said. > >

> > But then he showed another chart with the inverse relationship. Rather than rewarding content that came close to violating the community standards, Zuckerberg wrote, Facebook could choose to start “penalizing” it, giving it “less distribution and engagement” rather than more. How would this be done? With more AI. Facebook would develop better content-moderation models to detect this “borderline content” so it could be retroactively pushed lower in the news feed to snuff out its virality, he said. > >  > > The problem is that for all Zuckerberg’s promises, this strategy is tenuous at best. > > Misinformation and hate speech constantly evolve. New falsehoods spring up; new people and groups become targets. To catch things before they go viral, content-moderation models must be able to identify new unwanted content with high accuracy. But machine-learning models do not work that way. An algorithm that has learned to recognize Holocaust denial can’t immediately spot, say, Rohingya genocide denial. It must be trained on thousands, often even millions, of examples of a new type of content before learning to filter it out. Even then, users can quickly learn to outwit the model by doing things like changing the wording of a post or replacing incendiary phrases with euphemisms, making their message illegible to the AI while still obvious to a human. This is why new conspiracy theories can rapidly spiral out of control, and partly why, even after such content is banned, forms of it can persist on the platform.

> > The problem is that for all Zuckerberg’s promises, this strategy is tenuous at best. > > Misinformation and hate speech constantly evolve. New falsehoods spring up; new people and groups become targets. To catch things before they go viral, content-moderation models must be able to identify new unwanted content with high accuracy. But machine-learning models do not work that way. An algorithm that has learned to recognize Holocaust denial can’t immediately spot, say, Rohingya genocide denial. It must be trained on thousands, often even millions, of examples of a new type of content before learning to filter it out. Even then, users can quickly learn to outwit the model by doing things like changing the wording of a post or replacing incendiary phrases with euphemisms, making their message illegible to the AI while still obvious to a human. This is why new conspiracy theories can rapidly spiral out of control, and partly why, even after such content is banned, forms of it can persist on the platform.